Progressive Movement: A History of the Democratic Party

Michael Kazin

BEING DISCARDED

Democrat Solutions to Income Disparity Fail

Credit: Lily Geismer

Though they claim to represent working people, Democrats have historically only represented working white men. It wasn’t until the 1960s that Democrats made a dramatic shift beyond what modern historians have dubbed “egalitarian whiteness,” and it wasn’t until the 1970s that they completely committed to women’s rights.

When this shift in strategy was implemented, the party became the political home of a majority of female voters and a plurality of Black people. It caused white people to leave, though. No Democrat had ever been elected president prior to 1948 without first receiving a majority of the white vote.

Never again would a Democrat win the presidency after 1964. Particularly devastating to the Democrats was the vote of white male workers, whose interests long characterised the party.

Two significant publications explore the practical and moral difficulties of resettling this diaspora. Michael Kazin’s “What It Took to Win” traces the history of the party back 200 years, to its inception. Lily Geismer’s “Left Behind” continues the story in the 1990s. Both authors agree that the labour movement is the binding agent that will help put Humpty Dumpty back together.

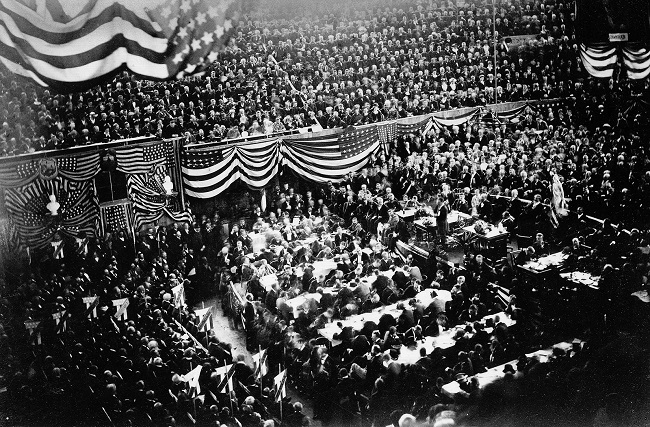

The Democrats are the “oldest mass party in the world,” as Kazin notes at the outset of his astute and thoroughly engaging history of the party. They were the first political group in history to regularly organise nominating conventions, the first to form a national committee and a congressional caucus, and the first to view party politics as more than just a necessary evil.

Despite popular belief, Martin Van Buren, a completely forgotten politician whose one-term presidency turned out to be the least interesting thing about him, was the true founder of this political system, as explained by Kazin.

In fact, Jefferson did form the Democratic-Republicans as an alternative to Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists; they are more often known as the Republicans today. This may cause some confusion with the modern Republican Party, which didn’t emerge until half a century later.

In all likelihood, Van Buren’s Democratic Party was influenced by the Democratic-Republicans. However, the opposing groups led by Hamilton and Jefferson were not political parties but rather caucuses. There were only about 10% of adult male landowners who could vote in 1800, therefore Jefferson “detested competitive political parties,” as Kazin points out.

Van Buren founded the caucus known as the Bucktails in 1813, shortly after being elected to the New York State Senate. Van Buren and the Bucktails were able to get rid of the need to own land in New York in order to vote.

In 1827, Van Buren, then a United States senator, collaborated with Thomas Ritchie, editor and publisher of The Richmond Enquirer, to combine “the planters of the South and the simple Republicans of the North.”

In honour of its first presidential candidate, Andrew Jackson, the group responsible for this action was formerly known as the “Jackson Party.” Twelve years later, however, the name was changed to the Democratic Party.

Planters in the South and “plain” (i.e. non-wealthy) Republicans in the North had more in common than would have been expected. Together, they detested Northern industrialists, high tariffs, financiers, and abolitionists. Working-class whites in the North (by the mid-19th century, largely Irish) weren’t any more eager than Southern planters to free enslaved Blacks because it would increase competition for jobs.

Protestant clergy were the most common type of abolitionist, and they often had little sympathy for the poor squatters who crowded their cities. “a horrible race of people for us to import and breed from,” the Boston-based anti-slavery Unitarian pastor Theodore Parker said of the Irish.

Twice in American History, the Democrats have Held Sway for Lengthy Stretches.

This was the “Age of Jackson” and “The Age of Roosevelt,” to paraphrase historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. The first one kicked off in 1828 and lasted until the eve of the American Civil War. The duration of the second period is roughly 1932-1970. Democrats won the White House in both time periods but only three times and held a majority in both houses of Congress.

In the lulls between, there were some severe power drops. No Democrat, other than Grover Cleveland, was elected president between Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 win and the turn of the century. The Democrats fared better in the wake of their second dethroning (perhaps because they avoided a Civil War defeat in favour of a Vietnam War defeat).

While the 20th century produced some formidable political machines, no modern president, not even Barack Obama, has ever led one as formidable as those who came before them. I don’t see why not.

The Solid South was no Longer in their Control.

Democratic Party leaders gave up on retaking the district after 40 years of trying. Lily Geismer’s “Left Behind” frames this tragedy through the lens of the Democratic Leadership Council, a non-profit founded in 1984 as a result of Representative Gillis Long of Louisiana, chairman of the House Democratic Caucus and nephew of the late Louisiana governor and senator Huey Long Jr.’s efforts to give the Democrats a more Southern flavour.

Its adherents argued for a reduction in bureaucratic red tape and the use of market-based responses to social issues. They eventually gained notoriety as the New Democrats. One of them, former Arkansas governor and Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton, utilised his position as the group’s chairman to help launch his political career.

The D.L.C. disbanded in 2011, making Geismer’s book a fascinatingly thorough account of a religion that no longer exists. She excels at documenting the development of the “microfinance” approach pioneered in Bangladesh by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus and enthusiastically adopted by both Bill and Hillary Clinton.

But the problem with microfinance was that very few low-income people, at least in the United States, could afford to take out microloans of a few thousand dollars at exorbitant interest rates to launch their own enterprises. Geismer says that a career that pays a living income is the best option for most people.

Geismer occasionally falls prey to the modern left’s desire to hold the New Democrats to an unrealistic standard. She cites Bill Clinton’s praise of the working poor who “played by the rules” as an example of his rhetoric that she believes stigmatises the poor who “supposedly did not.” I probably wrote “Oh, please” in the margin three or four times.

Bill Clinton’s most ambitious proposal, Hillarycare, was vetoed by a Democratic Congress that rapidly went Republican, and this is in part why the New Democrats weren’t evil but rather cautious.

Both Kazin and Geismer agree that the Democrats’ major issue is that they have lost power and purpose as a result of their separation from the labour movement.

Union membership increased from 3 million in 1933 to 15 million in 1945, mostly due to the labour safeguards granted early in Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency. A chapter on the New Deal by Kazin is headed “An American Labor Party?”

Unfortunately, that didn’t last very long. George Meany, who took over the newly united A.F.L.-C.I.O. in 1955, was a smug mediocrity, and Adlai Stevenson, a two-time presidential nominee of the 1950s, was inexplicably apathetic to labour.

The Effects of International Trade Were Felt Worldwide.

In 1947, however, the anti-labor Taft-Hartley Act was passed by Republicans and Southern Democrats over Harry Truman’s veto. This law severely limited union recruitment efforts. Since the 1950s, the percentage of private-sector workers who are members of labour unions has steadily declined.

The Democrats eventually stopped caring about workers and began actively courting Silicon Valley and college-educated city dwellers. According to Geismer, “the New Democrats consciously sought to limit the impact of the labour movement.”

The Democrats made a monumental mistake in 2016 when Donald Trump proved to them that urban, college-educated voters weren’t enough to elect Hillary Clinton.

Four years later, in 2024, the Democrats would elect their first really pro-labor president since Truman. The present leader of the free world would like to see labour unions revived. If Congress gives him the green light, the next three decades could be remembered as the Age of Biden.