A lot may be learned about the surface of objects through sculpture. How a muscle contracts, a robe falls over a knee, and breasts rest on a woman’s body are all things that may be learned from a study of classical sculpture.

Two Artists’ Divergent Roads to Eros

Additionally, contemporary sculpture is capable of: The monumental tectonic works of Richard Serra disorient and reshape the viewer’s perception of gravity and volume (and mortality, if one is up for it).

Koons’s balloon animals, made of stainless steel, bring to mind the underlying perversities of the mundane. No matter how much the focus of sculpture shifts over time, it still largely concerns the exterior world.

The material’s hard texture, its impenetrability, is what gives Serra its earth-moving effect. The steely shine of Koons’s work functions like a grin painted on someone’s face, contributing to the piece’s underlying sinisterness.

The accuracy of the chisel is demonstrated in a frothy, curled mound of hair that is stone cold permanent in a marble sculpture. Forming a sculpted physique is challenging. They may break into pieces, but they will not open.

How, though, would sculpture depict a body that could split open?

In what ways could this gap be shaped? Artwork by Eva Hesse and Hannah Wilke, two of the featured artists at the recently opened Erotic Abstraction exhibition at New York’s Acquavella Gallery, provides some insight into this subject.

It makes reasonable, from a biographical standpoint, to try to draw connections between the artists. They share a brief birth year, being born in 1936 (Hesse) and 1940 (Wilke). They shared a Jewish heritage and each experienced tragedy early in life:

Hesse escaped Nazi Germany to New York in 1939, her mother committed suicide when Hesse was 10 years old, and Hesse herself died of a brain tumour when she was 34. Wilke, a New York native, felt like death was all around her after the Holocaust, her father’s unexpected death when she was 20, and her own terminal cancer diagnosis at age 52.

There is no proof that these two artists ever met, yet their careers as painters and sculptors (and, in Wilke’s case, performance artists and filmmakers) in 1960s New York City overlapped.

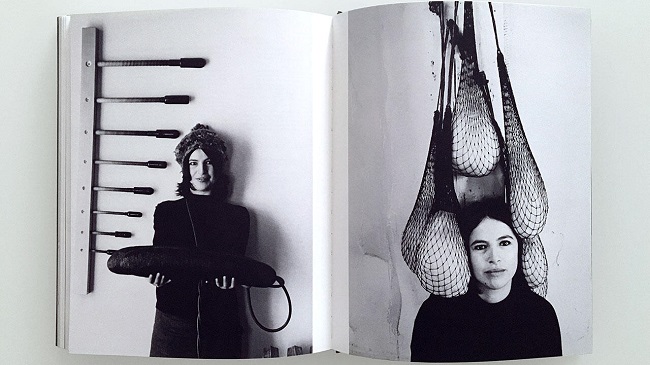

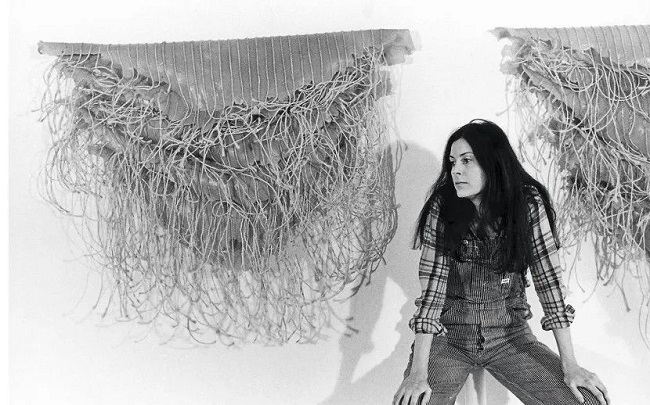

Incredible photographs of Hesse and Wilke at work are featured in the exhibition catalogue. Standing or crouching among liquid latex, fibreglass, and oddfound objects, both artists are hard to miss.

The emergence of such radical, ungainly materials in the late ’60s was a clear indication that minimalism, the reign of rigid, “inorganic,” geometric forms, was giving way to a more “organic” aesthetic. More “uneven” and obviously process-driven art was replacing the pristine (or boring, depending on your perspective) geometric forms.

Unlike Donald Judd’s boxes, which may seem like they were moulded and varnished by a platonic form, the art of Hesse and Wilke was inherently human. The results of their labour are not predetermined but rather the subject of an open inquiry.

This is the crux of Wilke’s main inquiry:

How many different ways are there to mould the vulva, using what materials, and for what purposes? To produce “a formal imagery that is uniquely female,” as Wilke put it, was a primary aim.

The gallery divides up Hesse’s pieces and Wilke’s, with the latter featuring an abundance of labial folds. Some of Wilke’s more blatant vulvic shapes are on display, including those fashioned of glazed porcelain, terracotta, and firmly kneaded erasers, which she has alternatively referred to as “cunts” and “gestural folds” in interviews (her bubble-gum and dryer-lint forms are not on view).

Ponder-r-rosa 1 (1974), one of Wilke’s latex-based abstract paintings, looks like a bouquet of sea flowers tacked to the wall in the background. The Orange One (1975) is a piece of art that longs to be touched on the right wall, and it consists of amoebic swaths of latex that have been bundled together with snaps. The body literally stretches out at you from every direction.

Although there is a lot of noise in Wilke’s art, there is also a silence. When looking at Untilted (around 1970s), one notices that not all of the seashell-like formations on the white wooden board have the same level of shininess.

The piece is made up of over 20 glazed ceramic vulvas.

Some are more transparent than others, revealing their inner workings (which are actually the inside of an inside) and revealing the concavities Wilke’s palm made by bending the clay in certain places.

Repetition of vulvar watching in the bedroom both desensitises the observer and prepares the vulva for action. It’s like a vulvic invasion as you reach the extreme end of the wall and find 62 small hand-pressed erasers affixed meticulously to a postcard of the Lincoln Memorial. That actually made me laugh out loud.

The same sorts of inquiries can be found throughout Hesse’s writing. In 1967, she was the first person to successfully incorporate latex into sculpture. The first time I read something by Hesse, I found it difficult to get my head around.

Like it knew something I wasn’t supposed to, like I wasn’t meant to know the secret it held. Where do I stand emotionally with Contingent’s vertical sheets of cheesecloth, latex, and fibreglass? What were the fibreglass and polyester resin cylinders with open lids of Repetition Nineteen III trying to tell me?

Then, finally, one of her pieces fit the key that opened all the locks.

Hesse’s Accession I (1967) is a massive steel container with no lid. On each edge of the box, hundreds of tiny holes have been drilled, and a rubber tube has been inserted into each one. What happens is sexual, to borrow the gallery’s phrase for it.

No, not in the stereotypical phallic sense (though there is an undercurrent of uninhibited flaccidity), but in a more literal, physical sense. As one examines the work, one is reminded of the painstaking effort required to thread each rubber tube through its corresponding small drilled hole.

A sense of relief, like pus forcing its way through a pore, comes from having been repeatedly squeezed through a small space. There’s also the overwhelming need to reach into the box and push your palms against the bulbous ends of the rubber tubes.

Even more striking is the similarity between these tubes and the fingerlike villi that border the intestinal tract. The piece has an internal effect; you start to feel tingly as it travels through you.

When visiting the gallery and entering Hesse’s room, visitors will encounter a plethora of intimate anomalies that are sure to set off more tingles. Plaster-dipped cords, electrical lines wrapped in fabric, bulbous halves are all present.

Extra strings (81) hang curiously from a Masonite board with a volcanic appearance that has been thickened with wood scraps (Iterate, 1966-67). A row of connected latex containers, the colour and texture of shed skin, is rushing down the wall (an exhibition copy of Sans III, 1969).

A shaky connection between her and Wilke emerges after only 10 minutes in the Hesse room. There is nothing on Earth quite like Hesse’s writing. Its vastness and vagueness surpass that of Wilke’s, and it has an air of cosmic folly.

However, it turns out that the artists’ professed differences in aesthetic “purpose” further disprove assertions of synchronicity. Wilke has noted, “By the time I was 20, I was aware that they were vaginas and we talked about it in college at the time.”

In the early 1960s, Wilke “worked in ceramics, constructing layered vaginal forms in natural browns and terracotta,” which Wilke says was a pivotal moment in her evolution. The vulvic shapes began to develop once [she] began using colour, namely pink ceramics, in about 1963.

On the other hand, Hesse is deliberately ambiguous when it comes to associating any clear picture with her writing. She aspires to be Gertrude Stein or Samuel Beckett in her diary entries:

Ideally, I’d have zero effort required of me at work.

It would therefore go beyond my expectations. By persevering, I will achieve the artistic goals I set for myself. The task at hand must involve more than this.

In order to expand my horizons, I must learn and understand more than I now do. The logical foundations are easily grasped. The quality of the unknown is the place and the thing I seek to escape. It gave way to its illogical nature as a thing or an object. There is some meaning to it, and there is no meaning to it.

Hesse, in interviews, graciously declined to have her work equated with or reduced to carnal themes or imagery. In a different diary entry, she says:

A Bag is a bag

A Semi-sphere – a semi-sphere

A Tube a tube

- Art is what is

- Tension and freedom

- Opposition and contradiction

- Abstract objects

- Not symbols for something else

- Detached but intimate personal

It does a disservice to both artists to link them as tightly as the curators would want, as Hesse’s cosmic extratextual work does not mesh with Wilke’s unique vocabulary.

In Wilke’s work, the raw materials appear to have been predetermined before they were formed, but in Hesse, both the shaping and the fate feel concurrent and spontaneous. The work’s repercussions are obvious.

However, to view them side by side is to get a complete sense of what it meant (and still means) to gleefully escape the canon, and of what it takes to be proudly unplaceable in the pantheon of art.

Something About The Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse, who was born in 1936, is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in American art of the 1960s.

Multiple large-scale solo exhibits over the past three decades, as well as a retrospective that visited the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum Wiesbaden, and the Tate Modern in London, are all testaments to the enduring appeal of her body of work.

To create works that could go beyond literal connotations, Hesse actively sought out and encouraged error, surprise, vulnerability, and enigma. The modest yet extremely charismatic things she created became pivotal in the development of contemporary art.