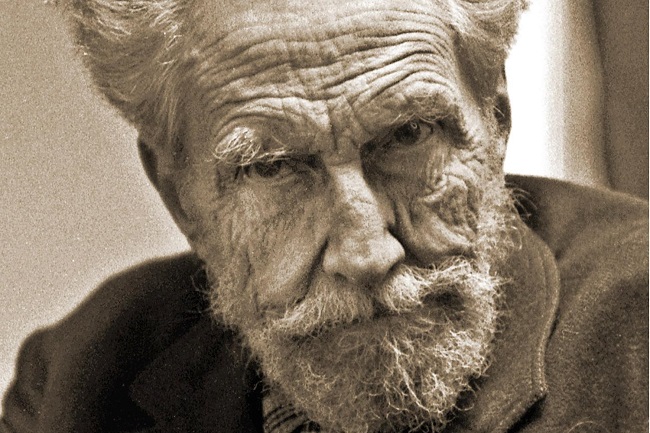

On October 30, 1885, Ezra Pound was born in Hailey, Idaho. He attended Penn for two years before transferring to Hamilton College, where he graduated in 1905 with a bachelor’s.

Ezra Pound interest in Japanese and Chinese Poetry

His interest in Japanese and Chinese poetry developed during his time spent overseas as the literary executor of the scholar Ernest Fenellosa in Spain, Italy, and London following his two years of teaching at Wabash College. In 1914, he wed Dorothy Shakespear, and by 1917 he was running the London office of the Little Review.

Pound relocated to Italy in 1924. When Pound returned to the United States in 1945, he was jailed for treason for broadcasting Fascist propaganda on the radio to the United States during World War II, which he had done while living in voluntary exile during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1946, he was found not guilty but sent to St.

Elizabeths Hospital in Washington

Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. due to a diagnosis of mental illness. Pound’s political activity was overlooked by the judges of the Bollingen Prize for Poetry (which included many of the most prominent writers of the day) in favour of acknowledging his artistic achievements, and he was granted the prize for the Pisan Cantos while he was in prison (New Directions, 1948).

Pound was released from the hospital in 1958 thanks to the efforts of several writers; he then moved back to Italy and resided in Venice, where he lived a secluded life until his death on November 1, 1972.

Many People Believe that Ezra Pound was the Primary Force in Developing and Popularising the Modernist Style of Poetry.

Famous for his support of great writers including T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and Marianne Moore, among many others, he facilitated a groundbreaking flow of work and ideas between British and American writers in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Last Words

The Imagist movement, which Pound popularised, was influenced by classical Chinese and Japanese poetry and aimed to “write in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of the metronome,” eschewing traditional rhyme and metre in favour of clarity, accuracy, and economy of language. For the next half-century, he worked on his encyclopaedic epic poem The Cantos.