In January of 2022, there were 2,436 people awaiting execution. The National Academy of Sciences reports that 4% of individuals on death row were wrongly convicted.

How a Death-Row Inmate’s Embrace of Conservatism Led to His Release

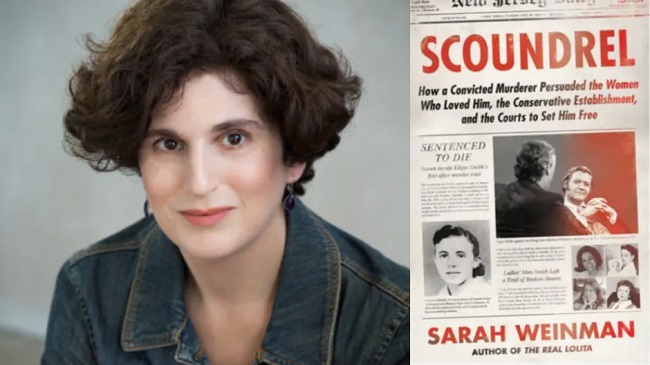

These injustices are frequently discussed in the media. A false conviction is not the focus of Scoundrel by Sarah Weinman. Instead, it’s an almost faultless depiction of a wrongful exoneration and the devastation it caused for everyone involved, including the victims of the criminal they helped free.

When Edgar Smith, then 23 years old and a married father of one, was found guilty of murdering 15-year-old Victoria Zielinski in the sleepy New Jersey hamlet of Mahwah in March 1957, he was a good-looking married man with a child. Angry, he took a baseball bat to her head and smashed her skull in.

Smith was immediately apprehended by police after they discovered blood splatter from Zielinski’s murder on his clothes and in the car he had rented on the day of the murder. He told police he drove the girl the night she was killed, but said she was still alive when he dropped her off.

This was before the Miranda decision mandated that suspects in detention be reminded of their right to stay silent. In an attempt to shift responsibility, he accused a close friend of the crime.

The jury convicted Smith guilty after deliberating for only two hours during a two week trial. On July 15, 1957, he received a death sentence and was sent on death row to await execution in the electric chair.

Then Came the Appeals.

When he was first put on death row at Trenton State Prison, no one anticipated Smith to survive as long as he did. In the meantime, he transformed himself from an unemployed blue collar loser into a phoney academic thanks to the gift of time.

He stayed informed with the news and current events by attending college. A 1962 newspaper article about Smith indicated that Smith admired William F. Buckley Jr.’s National Review. Buckley, a conservative legend, was so mystified by this that he handed Smith a lifetime subscription to his magazine for free (so to speak).

So started a decade-long correspondence in which the con artist successfully convinced Buckley and other members of the literary and judicial elite that his conviction was unjust. Buckley published an important piece for Esquire titled “The Approaching End of Edgar H. Smith” on October 19, 1965.

In it, he argued that the prosecution had the wrong guy, asked for money for Smith’s appeal fund, and promised that his fee would also be donated. Buckley even managed to get Williams and Connolly, one of the best criminal legal firms in the country, to represent Smith pro bono.

Smith was extremely skilled at deceiving others and manipulating situations, hallmarks of a psychopath. Brief Against Death, his narrative of his erroneous conviction, was published by Alfred A. Knopf (with a $10,000 advance, $75,000 in today’s dollars) thanks in large part to Buckley’s support and his own writing skills.

To woo his middle-aged married Knopf editor, the miserable Sophie Wilkins, Smith used flattery in his letters. In time, their business correspondence became sexually explicit to the level of a high school exchange.

Further, etc. His greatest win, however, came in 1971, when he convinced a federal appellate court to overturn his conviction and allow him a new trial on the grounds that his confession had been coerced. Smith, unwilling to take his chances at trial again, admitted guilt and received credit for time already served.

After His Release From Jail,

Buckley had him on his talk show, “Firing Line,” and he also had interviews with David Frost, Mike Douglas, Merv Griffin, and Barbara Walters.

On camera, Smith recanted his guilty plea and claimed he had to do it to beat the rigged system. Speaking for $1,000 at prison-reform conferences and universities about his time on death row extended his 15 minutes of fame.

Smith, who had problems controlling his anger, and his most ardent supporters faced a difficult time in the real world.

Even though he and Wilkins drifted apart (had he duped her into championing his book, or had she used him to rescue her sagging publishing career? ), another former prison pen pal entered into a relationship with him and was scared out of her wits when, within a year, Smith drove her to a secluded, heavily wooded area after an argument; she feared he would kill her.

When they got back to the house and he had cooled down, she still wouldn’t talk to him. Smith married a young woman (then 19) he had met and abused in a bowling alley in 1974.

Due to the fact that Smith appears to have only one story to tell, his writing career quickly dwindled, leaving him with few viable job options after moving to the San Diego area with his second wife.

These included security guard, parking lot attendant, dishwasher, and ad salesman for a local newspaper. He had rent arrears and tax arrears to pay. He also stopped making payments on an a few thousand dollar bank loan that Buckley had guaranteed.

In His Final Act of Robbery,

Smith kidnapped a woman at knifepoint from outside a factory on October 1, 1976. She fought back as he drove her onto the highway, and he sank the knife into her chest, missing her heart by a hair’s breadth.

When she persisted in resisting, he lost control of the car, she fled, and he drove away, but not before a bystander recorded his licence plate. Strangely, the woman managed to stay alive.

Smith ran away, crossing the nation in a series of zigzags to elude capture. In a Las Vegas hotel room after being on the run for two weeks, he made contact with his benefactor, Buckley. Later, Buckley reported him to the FBI.

Buckley stated, “I believe now that he was guilty of the first crime,” in the “On the Right” column dated November 20, 1976. Smith was found guilty of attempted murder and kidnapping in March 1977 and given a life sentence without the possibility of release. On March 20th, 2017, he passed away in Vacaville’s California Medical Facility, a prison. He was 83.

A Familiar Tune Plays in Our Heads.

Jack Abbott, a convicted murderer, was famously pushed for publication by Norman Mailer. In addition to publishing Abbott’s work and advocating on his behalf before the parole board, Mailer was instrumental in facilitating Abbott’s early release from jail in June 1981.

Abbott, after being released from prison for a month, killed a guy with a knife outside a restaurant in Greenwich Village. To Sophie Wilkins, Buckley remarked, “At least ours had the decency to wait a few years, and to botch the job.”

Why a criminal’s ability at spinning a phrase confers on him an aura of innocence — at least to the more naive among the literati — is a question Weinman’s book doesn’t answer, maybe because there is no solution.

Is it because their egos are so big that they can’t fathom that another writer wouldn’t be an upstanding citizen? That a stickler for the law like Buckley has assumed Smith’s mantle is especially jarring.