Two astute American playwrights renamed Henry James’s masterful novel Washington Square, about a rich girl, a dominating father, and a feckless lover, as The Heiress.

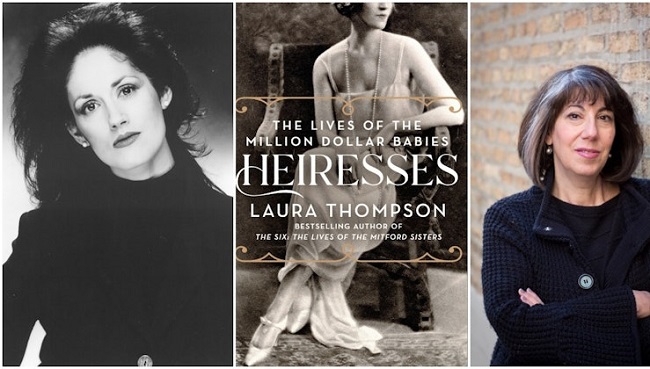

‘Heiresses’ Adds Up the Melancholy and Danger of Inherited Wealth

The dramatists were experts at what they did, just like the book’s author, Laura Thompson, whose study of women who’ve inherited large fortunes is both peculiar and riveting. Want to see a drama about a rich widow, a greedy businessman, or a mysterious heir?

Likewise, I wouldn’t do that. Sometimes, it’s the heiresses’ mistakes that make them the most interesting. As a result, they err in their judgement.

Almost without exception, Thompson’s helpless heroines did, with the exception of a few unlikable toughies whose goals were primarily altruistic. It would appear that one could always purchase a prominent position at a king’s table if they had enough money.

As the Married Woman’s Property Act of 1870 protected the assets of married women, fortune hunters used to resort to kidnapping young heiresses to get their hands on their money.

The Westminster estate was built on land that belonged to Mary Davies, a young woman who had been kidnapped by a malicious priest and remarried to his brother while under the influence of drugs. Mary was a widow and, more controversially, a Catholic who supported the exiled James II.

Davies was rescued by her Grosvenor heirs and instead of being murdered, she was sent to live the remainder of her days in a mental institution in the country. However, Thompson poses the question, “What if Davies had been a little less gullible?”

She uses Margaret Harley, a virtuous bluestocking heiress who married her duke for love, donated to Coram’s Foundling Hospital, and established Europe’s preeminent natural history museum at Bulstrode Hall, as an analogy.

Heiresses is Notably Lacking in Stories of Enlightened Heiresses.

Thompson did include Angela Burdett-Coutts, who was called “the best woman in England” for her groundbreaking work in London’s East End during Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee before marrying a man less than half her age and living happily ever after.

It’s fantastic to see Nancy Cunard being given credit for her commitment to causes. (In response to her concern about the Spanish Civil War, her friend Samuel Beckett famously wrote, “UP THE REPUBLIC!” in his translation of an essay that had been submitted to Negro, Cunard’s landmark 1934 celebration of black achievements.)

Is there no room for the modern female philanthropists like Vivien Duffield, Sigrid Rausing, and Jasmine Whitbread? Lady Byron (the poet’s vilified widow) and her groundbreaking work in co-ed institutions like schools and prisons doesn’t get any respect around here?

Thompson, on the other hand, presents a study of rich ladies with leisure time that is rife with rumours and snark. The marriage of Consuelo Vanderbilt, heiress to a fortune, to the little but titled owner of one of England’s largest and most miserable estates (Blenheim) is a prime example of a transactional union.

Vanderbilt, like fatherless heiress Daisy Warwick, found solace in partners (her promiscuous husband called her “the old tart”) and later politics, unsuccessfully running as the Progressive party’s “Mrs. Marlborough,” until finding true love with a French aviator.

Warwick, a Socialist who ran against Anthony Eden in 1923, enjoyed showing the bed she slept with a king to the leaders of the Trades Union Congress.

Thompson’s stories of the heiresses who never found a cause are less enlightening but unwholesomely fascinating. When her lovers abandoned her, Alice “Silver Spoon” de Janzé began shooting them and ultimately took her own life.

Barbara Hutton, who had millions thanks to the Woolworth workers, spent her time shopping for spouses and had seven before she died of a heart attack when she had almost spent her whole fortune.

Thompson spent time in Covid isolation with a group of confused heiresses; what did she learn? Is she at the point where a large sum of money may make her happy?

Enough, she seems to imply, to live in many mansions, fund an animal refuge, buy a picture by Stubbs, and build her own cryonics chamber. She humbly acknowledges, “I guess,” that “it might.”