In the two centuries since 1817, there have been seven major worldwide outbreaks of cholera, and the most recent one appears to be here to stay.

The disease seems to have won because to the combination of warming temperatures and a particularly resilient and toxic strain of bacteria.

Battling an Ancient Scourge

In response to these epidemics, public health professionals are developing vaccinations, fighting to improve sanitation in developing countries, and groping for answers as to how to predict the next outbreak.

One group of scientists has proposed utilising satellites and sari cloth in an effort to combat the pandemic.

This pandemic began in 1961, while the others lasted between five and twenty-five years. We’ve been going through this for fifty years now, and it shows no signs of stopping. It’s picking up speed, according to Edward T. Ryan, MGH’s director of tropical medicine. Our commitment is long-term.

The virus first appeared in Indonesia in December of 2002, then swept over South America in 1991, and has continued to erupt in deadly events on a regular basis ever since. After the devastating earthquake in Haiti in 2010, the doors were wide open for a pandemic that would eventually claim the lives of some five thousand individuals.

Between those years, over 10,000 people perished in Zimbabwe. Vietnam, Angola, Sudan, and Somalia have all seen illness outbreaks, and Pakistan’s recent flooding has triggered an outbreak there as well.

Peter Hotez, from the Chicago-based American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, noted, “We are witnessing these extended outbreaks spanning months and years.”

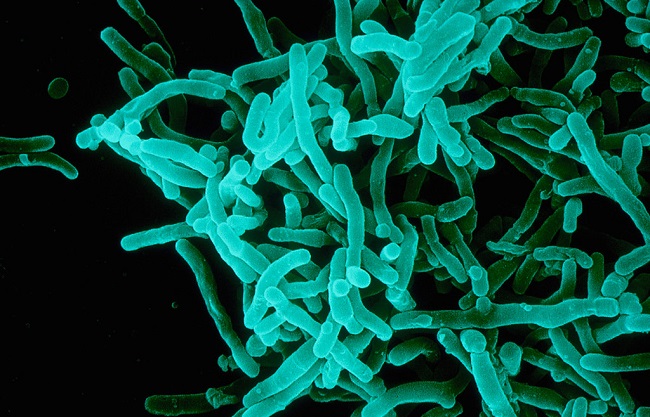

According to experts, a new strain of the cholera germs has emerged that is both more dangerous and more resistant to treatment than any previously observed.

Cholera is a Disease That Can Cause a Rapid And Unpleasant Demise.

Diarrhea so severe that it causes rapid loss of body fluids and subsequent dehydration and shock can occur within 24 hours following bacterial ingestion in a person with the condition. A serious infection carries a mortality rate of almost 50% if the afflicted person does not receive medical attention soon.

Former director of the National Science Foundation Rita Colwell has studied cholera epidemics for many years. She is now 77 years old and has been acknowledged as the detective who discovered where cholera hides in between epidemics, earning her the Stockholm Water Prize in 2010.

Colwell, a professor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland, said that deaths from cholera are “absolutely senseless.” The disease has a mortality rate of less than one percent if treated promptly with basic salt and sugar solutions.

Cholera is typically spread through contaminated drinking water or the consumption of contaminated seafood. When a disease spreads rapidly in a country with poor sanitation, local health authorities may be unprepared to handle the situation.

Colwell was instrumental in clarifying the causes of the occasional spread of cholera in the late 1960s. Cholera bacteria can persist in a dormant form in tidal waters and estuaries, which she unexpectedly found in the Chesapeake Bay. When the water temperature rises, more phytoplankton and zooplankton flourish, and the bacteria adhere to them and multiply.

In turn, this can cause an outbreak in locations with inadequate water sanitation systems, as infected waters are mixed with fresh water due to high tides, strong rains, or flooding. Because drinking water is purified, no one in the Chesapeake Bay area has noticed.

Harvard University’s Center for Health and Global Environment associate director Paul Epstein credited Rita with “deserving the ultimate credit” for discovering the cholera reservoirs after decades of searching for them.

Colwell and others have been trying to anticipate the bacteria’s breakout ever since they found its hiding place. Colwell discovered that detectable oceanic changes typically occur around six weeks before an epidemic. As a result, she now actively promotes the usage of cutting-edge innovation.

Because of the sensors on board satellites, we are able to accurately detect chlorophyll, sea surface temperature, and sea level. It turns out these indicators are really helpful in forecasting cholera epidemics,” she remarked in a recent interview.

In a study published this month, Mohammad Ali, a senior scientist at the International Vaccine Institute in Seoul, discovered that increasing air temperatures and rainfall frequently follow outbreaks. Based on the seven years of data he collected in Zanzibar, he found that “quite close to the prediction” is how the data actually turned out.

Epstein, whose new book “Changing Earth, Changing Health” discusses the health risks posed by climate change, noted that the increase in cholera from even slightly higher temperatures is an unsettling association as climate change warms the planet and causes heavier, more frequent downpours.

It is the Most Important Illness Spread by Water.

“Climate-related precipitation and sea-level rise pose the greatest hazard worldwide,” he warned. Improvements in forecasting “may prevent many deaths.”

Colwell concedes that prediction is useful, but that it is not sufficient. Local health officials must respond quickly if the conditions are favourable for an epidemic.

There are two vaccines, but they both need to be administered on separate occasions, making them useless once an outbreak has begun. Colwell points out that in countries with low living standards and few resources, the simplest solutions are sometimes the only ones accessible.

Conclusion

From 1999 to 2002, she advocated for women in Bangladesh to use a folded, cheap sari cloth (like to a cheesecloth) to filter water as they carried it. The cholera cases dropped by more than half after that easy change, she discovered.

Even after three years, the women were still employing the technique. They realised they and their infants weren’t getting sick. So, I didn’t need much prompting.”